Table of Contents

Two Poems - Aaron Ivsin

The bitter taste of coffee, rising -

The face of a full moon, resting -

The bed of a truck, sitting down.

Watching the ashen plumes of goldenrod,

the trace of maple canopies,

the broken plane of a beaver pond

recede down a winding road -

See no deer, hear no owl.

The wind passes over my ears.

Posted 18-Oct-2024

Xin Qiji

I have seen that mystery there, reclining,

ball in one hand, long dart in the other,

and heavy measure on the table.

She sits on dun wicker, by a long pane

of reradiated Autumn heat. She smiles

and tells the story of Grandfather,

his time in the underworld

and the noise there ------ A

dream of circumpolar sea

when it is warm,

when birds land,

and a chest is full of linen.

I have seen that mystery there, reclining,

when an old man wakes and says:

"What a cool and lovely Autumn."

Posted 13-May-2024

Frederick Jameson's "An American Utopia - Review and Response

When I first read this essay, I found it provoking and resonant at times, but deeply scattered. I still have no close familiarity with many of the psychoanalytic concepts it was using and was confused by the utter absurdity of the main idea, the titular Universal Army. When I was rereading and reviewing it more closely in preparation for writing this small review however, I began to connect strongly with the emotional thrust of the essay. At the end, I grasped that the hundred-odd pages Frederick Jameson wrote are really the notes to a much more substantial novel that a different writer would have produced.

In the following paragraphs I outline the main points of the essay. This is not a critical commentary, but a summarization I formed to check my own comprehension and to feel the resonances of the original writing.

Frederic Jameson frames the essay "An American Utopia", as so many seemed to enjoy doing before the summer of 2020, by talking about the political stagnation of the moment, the lack of far-reaching political organization, the collapse of the left, the end of history, etc. His proposal to counteract this is a rehabilitation of socialist demands in the public sphere and the return of Utopian imagination. The principal demands he makes are such: nationalization of all financial institutions, the seizure and nationalization of energy sources, an end to inheritance, great taxation of the wealthy, a general program of wealth redistribution, a guaranteed annual minimum wage along with full employment, abolition of NATO, prohibition of right-wing propaganda, free health care, reinvestment in education, and the mass abrogation of debts. I stand by all of these, and I understand the feeling of hopelessness which sometime undercut their advocates, especially in this world of mass surveillance and mass incarceration. But Jameson doesn't believe that the presence of these demands in the political sphere, in the mouths of candidates, will lead to their enactment - it isn't a reformist position. Instead it is a rejoinder that the demand for demands is the basis of any political opposition. Utopianism, as the summit of demands, will make a path for the transformations we seek.

The vehicle for his Utopian exploration is the Universal Army, a supposedly dual-power institution that emerges out the current political schema and carries out the destruction of the state, the transformation of society, and really institutes all of the socialistic demands that the state is unable to. The Universal Army's universal enlistment (all those aged 16 to 55, regardless of ability or status) provides the foundation on which a revolution in the healthcare system is conducted, pushed along by the requirement to provide socialized medicine to all those enrolled. It will go on to transform post-secondary education, scientific research, creative activity, and all economic aspects of life. Also of note is that the distribution of tasks and responsibilities will be based entirely on a system of lottery, of which I will write more later (for some further ideas on the possibility of lottery-based, mass organization of duties and conflicts, I would refer you to C.L.R. James's peculiar little 1956 essay on the ancient Greek democracy, "Every Cook Can Govern", which I link here). But let Jameson describe the Army:

"We may also assume a reorientation of education itself under military auspices, not merely for the children of this military population but for various advanced degrees. Nowadays it is difficult to think of any kind of advanced training, save perhaps for business schools, that would not be required within this system (the Army Corps of Engineers is the obvious example). We may think of the socialist (or ex-socialist) countries for models of our situation, in which the various armies included such functions as the manufacture of clothing, the production of films, the eventual production of motor vehicles, and even (as in China) a writers' union, in which intellectuals and writers and artists found their space and income. The army is also notoriously the source of manpower for disaster relief, infrastructural repair and construction and the like; the question of food supply would immediately place this institution (if it can still be called that) in charge of the ordering and supply of food production and therefore in a controlling position for that fundamental dietetic and agronomic activity as well"

It will be useful for everything but warfare. Jameson is not advocating for universal participation in the genocidal war machine that is the US military (the resulting mass of people after universal enlistment would also be so unmanageable it wouldn't be useful for warfare, he notes). "Pacifists and conscientious objectors would be placed in control of arms development, arms storage, and the like." The reason he chooses the Army, then, rather than the post office or a labor union, is due to its relationship to the American legal system and its federalist organization. Jameson has supposedly written more extensively about the "federalism problem" elsewhere, but he annoyingly declines to cite himself. It feels slightly underelaborated in this essay. He reiterates that the American constitution is a foundational fetish for political organization and a tremendously counterrevolutionary device, serving to ameliorate tensions between classes by diverting them into negotiations between representatives of a false geographic organization. I don't doubt this and ultimately it isn't particularly relevant. What is elaborated in this essay is the problem of interpersonal federalism, the formation of small petty competing social groups. It also seems like another way of describing the social problems of class stratification. One of the functions of wealth, Jameson writes, is the isolation of the wealthy from particular classes and individuals. The purchasing of behavior, the commandment of lackeys, the construction of separated infrastructure, ghettoization - all reflect this basic repulsion of one's fellows that the wealthy are able to satisfy. The Army takes this possibility off the table.

"A final motive for anti-Utopian resistance, particularly in the area of armies, military service, and the like, must be sought for in a deeper place, which is neither a psychological nor a metaphysical one, I would argue, but very much an instantiation of Sartre's famous conclusion: Hell is other people. It is an originary trauma which explains the function of small groups as protection and which, no doubt, few enough of us are willing to face directly. Those who do have often reached the sobering assessment that the human species is a particularly loathsome biological entity, and this very much owing to its individuality (and freedom) rather than its lack of it. (The idea that humans are naturally good and altruistic is then a secondary corrective to this first metaphysical reaction.) This is why the rich are primarily motivated not by power or pleasure, but by the possibility of radical isolation, of separating themselves off, by way of bodyguards, private property, walls, and the like, from their fellow men (and women).

"The army is virtually the only institution in modern society whose members are obliged to associate with all kinds of people on an involuntary, non-elective basis, beginning with social class as such. This forced association, initially restricted to males, has been a useful mechanism, in the age of nationalism and the modern nation-state, for securing a certain collective unification and leveling (including the imposition of a national language). So the army is the first glimpse of a classless society, with all the anxieties such a novel social situation has historically (and inevitably) aroused."

We shouldn't forget, central to these harmonious, energizing, and Utopian feelings, will be the enormous destruction of abundance and privilege which rotting in the core of this society. At the climax of the struggle between the old governments an the new Army will be enormous reparative acts, which will consist not only of organized transfers of capital, labor power, and resources to those impoverished and victimized regions of the globe; but also monumental acts of looting, direct seizure, jubilee and potlatch. Guy Debord, writing about the riots in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, says: "once the vaunted abundance is taken at face value and directly seized, instead of being eternally pursued in the rat-race of alienated labor and increasing unmet social needs, real desires begin to be expressed in festive celebration, in playful self-assertion, in the potlatch of destruction." After these events, we will once more declare: "now for the first time the problem is not to overcome scarcity, but to master material abundance according to new principles. Mastering abundance is not just changing the way it is shared out, but totally reorienting it. This is the first step of a vast, all-embracing struggle." The Universal Army will then cease to serve as an actual institution, a physical bureaucracy or identifiable collection of people and activities, but a cultural thread at the heart of the species; a Zugenruhe instigating the circulation of huge masses of people and the collective fulfillment of desires and social needs according to communist principles.

The new world is not without conflict, but the conflict will be changed; it will be interpersonal, internecine, and factional. Conflicts will occur because of the sheer dislike one human being can feel for another, and the new possibility of conflict will be constantly provoked by the Army. The other institution of the new society, or the other facet of the Universal Army, is the "Psychoanalytic Placement Bureau", the dispenser of individual and group therapies, combining "the functions of a union and a hospital, an employment office and a court, a market research agency, a polling bureau, and a social welfare center." "Computer calculations" figure in here, somewhere, as a necessary component in figuring out the problem of social reproduction - he doesn't go much further and I will let the sleeping dog lie. What is important to grasp is that the therapy the Bureau dispenses is really treatment for anti-Utopian impulses plaguing the current society, a "therapy for dystopia". The first dose is his essay.

Jameson imagines a world split explicitly into absolute necessity and absolute freedom. One way to imagine this is a temporal division of activity, where only mornings, or odd-numbered weeks or months, are given to participation in computer-and-lottery ordained responsibilities, conducted in common with other members of the Universal Army. This is accompanied by uniform dress, standardized language, military organization, etc. Nights, or even-numbered weeks or months, are given to freedom. This could consist of wholesome activities (polite cultural production, "self-improvement", etc.) just as well as interpersonal antagonism, drug use, or any other frippery. This is accompanied by a universal drama and pastiche in behavior and dress, cants and nonsense, rowdy and undisciplined behavior. The division might also be spatial - he cites Samuel Delaney's Triton and its "unlicensed sector" of complete permissiveness as one example of this. He describes the realm of freedom:

"In the world of the superstructure, no such specifications hold; the individual is as free to be a recluse as a party person, to practice hobbies or to live out existence as a couch potato, to be a family man or professional mother, to volunteer for hospital work or to climb mountains or to struggle with drug addiction, to gamble on the stock market (some new form of value competition to be invented here) or to write books, to conduct church services, to become a saint, or to live whatever underground life can still be invented. For the superstructure is a matter of invention; and to begin with, one expects its practitioners to distinguish their choices by the most extravagant garments. This is a wholly secular world, in which, as Sartre taught us, everything is performance, everything is social construction. Our existential anxiety lies in the palpable fact that we are always at some slight distance from our choices (and free to change them at any point) and that, in that sense, there is no longer any human nature or any personal identity to weigh us down and offer the security of being one single unalterable personality."

In every way, the new society will "welcome the most outrageous self-indulgences and personal freedoms of its citizens in all things, very much including puritanism and the hatred of self-indulgence and personal freedoms". And no one will be satisfied:

"From this condition-which is neither an emotion nor a political motivation, but rather a structural possibility and an existential fact - to the more generalized conviction about "antagonism" there is but a philosophical step, for antagonism simply denies the possibility of the "cure," whether societal or individual. It denies the possibility of social harmony, whose peaceful regulation was promised, for example, by the various systems of democracy (but also offered by Hobbes's sovereign), thereby opening a path to the construction of a utopian social order that embraces antagonism as such, although perhaps not in so mechanical a way as in Callenbach's War Games. Or better still, as has been suggested above, it excludes the aims and projects of political theory altogether and allows human relationships to develop in other ways."

Like the Universal Army, the Psychoanalytic Placement Bureau will not be a physical institution, a collection of bureaucrats and formal techniques, which must be maintained year to year and shielded from the torments of antisocial freaks. Rather it will be the final product of a cultural revolution establishing the primacy of conflict as the fundamental substance of human life. With it will come monumental new cultural production of rebellious, destructive, and factitious groups along with novel forms of friendship and good humor. These new methods for rebellion and mediation, and their constant reinvention, are the products of that "total reorientation" of abundance Debord declared earlier.

In one of the many off-hand sections of the essay, Jameson notes with good humor that one of the models of the new kind of conflict to come is the High-School movie, where the suspension of necessary labor allows pathology and insane conflict to take center stage: "The high-school film, then - with all the unpleasantness of its various group bondings, its competitions, its hazing and its exclusions, indeed its unmotivated friendships and enmities, … will come to be acknowledged as a revealing expression of the deepest Utopian impulses". During my own secondary education, I was fairly conscious of the social reproduction taking place during our eight periods; of the aspects of physical and psychological conditioning and its place in the whole scheme of my life long ago laid out. This understanding could sometimes ameliorate my natural feelings of rage, resentment, and frustration at being in such a situation, but it never could over come them. That overcoming was only ever hinted at during the year of my graduation, 2020, when the demonstrations and destruction forced some feeble and tentative concessions from city leaders; enough to provoke even my most fearful peers into considering the possibility and necessity of new arrangements, and giving us others the chance to insist on the most totalizing transformations.

Posted 21-Dec-2023

The Triple Helix - Richard Lewontin

Richard Lewontin's "The Triple Helix" is principally concerned with breaking down two dogmatic principles in biological thinking: that environments determine genotypes, and that genotypes determine phenotypes. Even in introductory textbooks, it is never expressed as unequivocally as this, and in our day-to-day lives we hardly live as if these relationships are so simple. Nonetheless, this simplified model of relations between environment, genetics, and organism, become fixed in our thinking over time, simplified after repeated uncritical usage in the classroom. Frequently they are explained through simple case studies; discussed at length in my high school classroom was the English black peppered moth, Biston betularia, which experienced a rapid and noticeable change in genotypic and phenotypic composition in response to a rapidly changing environment. When discussing genotypes, some of our lessons modeled the experiments conducted on Drosophilia flies, a very common medium of experimentation for developmental and genetic biologists.

These examples are not false, and neither are the basic principles they explain. However, if we want to be good biologists, we must come to fully understand the complex interpenetration of organisms, their genetics, and their environment.

The genes of an organism are a fundamental input in the outcomes of its development, Lewontin admits. The connection between a particular gene and a particular phenotypic outcome, however, is extremely convoluted. Most distinguishing phenotypes are directly influenced by a large number of genes, and indirectly by an even greater number. More importantly, an organism’s environment significantly affects the way genes are expressed. Genetically identical organisms can have significant developmental variation when placed in different environments, or even when placed in the same environment! And some genetic variation, while producing developmental variation in some environmental conditions, does not produce developmental variation in other kinds of environments!

These facts are made even more complex when we consider mechanisms of natural selection. For example, a species may possess a mutation of a particular gene that generally produces a desirable physiological change, improving the fitness of the species. Over enough time, we would expect this variant in the organism to become dominant, resulting in evolution of the species. There may be a second mutation, of a different gene, that also produces a desirable change, also improving the fitness of the species, etc. It is not uncommon, interestingly, for these two desirable mutations to interact negatively, meaning the presence of one or the other is beneficial, while the combination of both is undesirable! This is precisely the situation in Moraba scurra, a grasshopper Lewontin examines to illustrate this point.

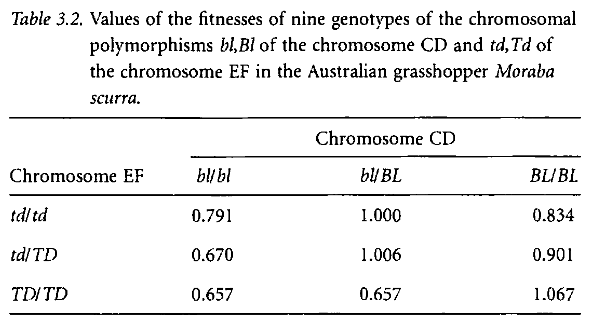

The first table illustrates the fitness values (how evolutionary fit) of given combinations of particular genotypes in this grasshopper. A higher value is a higher chance of surviving and passing on those particular combinations, and vice versa. One genotype is not universally preferable; its fitness always depends, in some complex relationship, on the other gene as well.

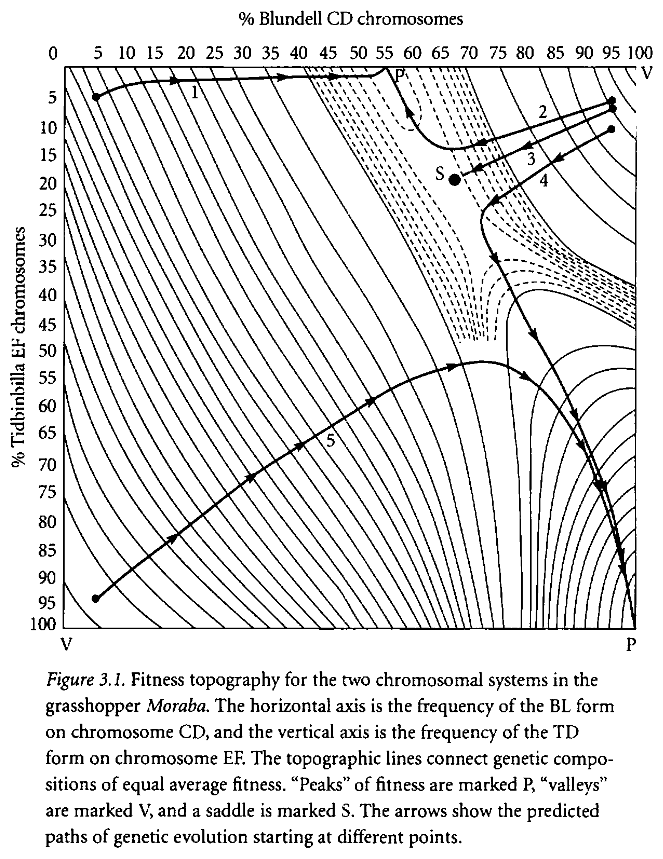

The second table illustrates the same point, with genes represented as percentages of the population rather than as specific combinations. The arrowed lines show the movement of the population average given various starting points; ie, change in genotype distribution over time. If, for example, if a population of grasshoppers began with a genetic makeup mostly possessing the TD/TD and bl/bl genotypes, (the bottom left corner), natural selection will produce first a population mostly consisting of td/TD and bl/BL genotypes, and only then for the more desirable TD/TD and BL/BL genotypes! It is not possible to move linearly from bl/bl to BL/BL, because the intermediate combination has a very low level of fitness. Similarly, given other starting points of genetic variation, it may be impossible to move to the most fit genetic type; this is the situation illustrated by the lines of motion in the top half of the diagram.

One can imagine how much more complicated this situation gets when there are even more kinds of genetic variations at play.

The more tricky relationship is the one between an organism and its environment. Lewontin begins this section by critiquing the concept of an ecological niche. Although a fundamental piece of our vocabulary in the ecological sciences, it does not hold up well to scrutiny. Behind the concept of an ecological niche is a static, unchanging environment, perforated in various places to allow organisms to "fit in". The roles available to play in a given system have already been determined by the environment. What is missing from this picture is the way organisms construct their own environments, and the way every organism is an element in the “environment” of every other organism! The perspective we ordinarily use reduces the organism to simple ecological function, rather than seeing them as unique actors.

In order to more completely understand organisms, then, we must see environments as the “penumbra of external conditions that are relevant to an organism because it has effective interactions with those aspects of the outer world” (pg. 48). Penumbra is an astronomical term that refers to the half-dark, half-lit region at the edge of a shadow cast by an object. What this view entails is that every environment is a zone of ambiguity, which is constructed partially by its organism and partially by the rest of material reality.

This is very easy to see in animals such as beavers, which literally construct their environments by building dams, raising the water table, constructing shelters, and changing the composition of woody plants in the nearby environments, as well as the composition of aquatic and semiaquatic species living in the modulated environments. Other situations may not be so simple.

Here is another example drawn from my own experiences: let us take the oak savanna ecosystems, which are frequently subject to human-induced wildfires. Mature oaks have thick bark which protects them from these wildfires, while many other trees are unable to withstand them. Dead oak leaves are thick, full of tannins (making them difficult to decompose), and persist on the tree for a greater time period. They also curl and are rigid; these all combine to create a humus which is airy, dry, and fuel-rich, which increases the frequency and intensity of fires!

It may be easy enough to say that the encouragement oaks offer to fires is not a result of their “activity”, but is simply determined by their genetics. This is not untrue. But, if we are interested in forming a more sophisticated research program, we might study, for example, what kind of changes in oak development are induced by it being exposed to a wildfire, or other environmental conditions. We might see that the changes the oak undergoes in response to its environment go on to affect the environment itself. We would have a dynamic system of parts always affecting one another, and then recieving their own effects through their surroundings; the causal relationships are circular, not linear.

Lewontin's book is full of more complex arguments and illustrative examples. I have attempted here to reproduce some of the more interesting and fundamental points, but I have hardly expressed the full scope or depth of the work. I would recommend it very strongly to any person studying, or even interested in any kind of biological science. Due to its age, and the frequent changes in these fields, I would not be surprised if some of the particular research discussed is slightly out-of-date; nonetheless, the fundamental problems discussed are still prevalent in so many of my classes today. I hope to make the kind of complex thinking he demonstrates useful in my own studies.

Posted 8-Apr-2023